Opinion | Sex Bots, Religion and the Wild World of A.I.

[THEME MUSIC]

(SINGING) When you walk in the room, do you have sway.

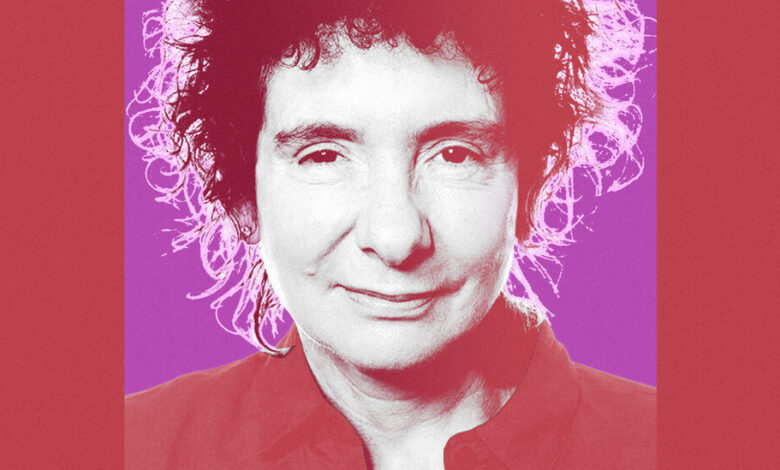

I’m Kara Swisher, and you’re listening to “Sway.” My guest today is Jeanette Winterson, the author of “Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit” and “Frankissstein.” Her latest book, “12 Bytes,” is a series of essays that imagines a future where artificial intelligence is smart enough to live alongside humans.

She explores how that would change the way we learn, communicate, have relationships, have sex, and even how we think about death. So far, IRL, the shiny digital future hasn’t turned out that well, at all, especially with tech bros like Zuck and company in the driver’s seat. But Winterson has a sunnier view of the possibilities. I don’t.

So I wanted to ask her why that is and what needs to happen to make sure we end up with an A.I. that doesn’t destroy us.

Jeanette Winterson, welcome to “Sway.”

It’s great to be here, even though we’re still in this virtual two-dimensional world of the blended reality that COVID has thrust upon us.

Or maybe it’s an opportunity.

Maybe it’s an opportunity.

So your new book out is called “12 Bytes.” There’s a lot in here, from Frankenstein to vampires, to Buddhism, to sex dolls and cryogenics. But as one reviewer put it — probably the most negative review you got — “Why should we care what Jeanette Winterson has to say about artificial intelligence?” So tell us. Tell us why that is.

You know, I’ve been working on the work that I do for nearly 40 years, and I’ve got a platform. And I think it’s my responsibility to talk about the big issues of the day, whether that’s climate breakdown, whether it’s social inequality, whether it’s the coming world of A.I. And for me, that’s my responsibility, and I hope that there will be folks out there who think, yeah, we’ve been on the journey with her a few times around the block, we’ll see what she’s got to say now.

And I hope there’ll be other folks who’ll say, well, most books about A.I. books about tech are quite narrow-goal. And this is a book where I wanted to multitask, because I wanted to bring in ideas about philosophy, religion, politics, and history, our past from the Industrial Revolution, which is the moment when life starts to accelerate.

This is how we got here now. So this came from a really straightforward premise in my head after writing my novel, “Frankissstein.” I need to explore this further. So how can I do that?

Right. And let me start with one thing that you just said. First, I’d love you to talk about the link between “Frankissstein” and this book, because a lot of the issues are the nonfiction version of things that you brought up there, including creating something out of nothing and this idea of not needing the body any longer.

Yeah, I wrote “Frankissstein,” really, in a response to Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” which turned out to be a message in a bottle, a prophetic vision. She imagined a time when humans would create an alternative life form. And hers was out of the discarded body parts of the graveyard. Ours is out of the zeros and ones of code.

But she had this astonishing insight that it would depend on electricity, which was not a force used in application. And the Industrial Revolution was about coal and steam, you know. Everything was heavy.

And our future, if it’s going to be sustainable, will be about creating sustainable electricity, which is the only power source that A.I. and its successor A.G.I., Artificial General Intelligence, will need. Look, it’s not going to eat. It’s not going to sleep. It’s not going to need bank accounts and yachts.

Our values are not going to be the values of what we’re creating. Once artificial intelligence ceases to be a tool, if it does, and becomes a player in the game, something alongside us, then Homo sapiens is no longer top of the tree. We’re going to have to revisit our own exceptionalism. And that seemed to me —

Which was the idea behind “Frankissstein,” right? The idea that they were trying to create a better human being, but of course it got out of control.

It got out of control. It always does with humans. We always manage to mess it up. And it may be that being chimpanzees with big brains has got as far as it can go.

You know, I’m hoping that this is a moment when Homo sapiens, which has been around for about 300,000 years on planet Earth, will evolve, first into the transhuman, and then into the posthuman. I don’t have a moral or ethical problem with that. I am sure that we can’t continue as we are.

Right. But talk a little bit of that concept, because you talk about it in the book several times — this idea of life continuing beyond the body, which is something you and I talked about with “Frankissstein.”

Yeah, and obviously, anybody who’s religious is interested in that idea. The question is, is consciousness obliged to materiality? Humans are embodied. That’s all we know.

You don’t get a human without a body. But sometimes our bodies are distorted or difficult. Lots of people hate their bodies. People have always hoped that something else, something essential survives the death of the physical body.

Science has always said, no, this is not true. This is magical thinking. Get over it. But now, science and religion have started to say the same things, that actually, yes, maybe consciousness is not obliged to materiality.

Maybe we could upload our brains. Maybe we could live much longer lives if we were blended, if we were transhuman. Maybe physical death at 80 or 90 is not necessary.

So we’re revising what it means to be a human being, and we don’t know where the limits of that are yet. But we do know that the idea that it’s not here, we’re not bound in our bodies, we’re not just confined to this planet, is now something which is the hot property of A.I. and where it might take us.

Now, if we were not subject to the present constraints of the body — and most of us have doubled our lifespan since, really, the early 1900s — people are living much longer. If we could do that again and again and again, we would have a different relationship to the biological body. But then, we might leave it behind altogether.

So it’s somewhat useless for —

Yeah.

Eventually.

I think, eventually, yes. And that is the question. Every culture across time since recorded history — the Epic of Gilgamesh, it’s that familiar story we all know. A guy has lost his best friend. What is death? What happens after we disappear? Is there — how can we bring back those we love?

It’s that story, which we know so well, and it’s always the one that’s troubled us. If now, science is not at odds with that story, if technology is saying that story could be real, then maybe we did always know, and that fascinates me.

So this idea — the first step is obviously transhumanism — how the body dies, the mind continues with a digital brain and possibly a cyborg concept, which is the singularity. I mean, I’ve heard it a zillion times in Silicon Valley. And you’ve talked about the human form as only provisional.

Yes.

So that’s the first step. Presumably, the second step is just a digital brain. Is there always a body? Is there always a form?

No, I don’t think there need be. I mean, just as with A.I. at the moment, we’ve got embodied, which is robotics, and non-embodied, which is operating systems. So it could be, with any future evolution of Homo sapiens or whatever mixed media Homo sapiens looks like — that if you want a body of some shape or form, you can have one.

And if you don’t, if you want to be consciousness — spirit, it would have been called at certain times — then you can. And we see this not just in religions but in all sorts of legends and cultures, the idea that the shaman or the magician can leave the body and enter another form, and then return to the previous form, or visit the astral world. All this is very common. And that’s why I wonder, is it so common because actually, it was always an intuition about where we would end up or what was likely for us?

Do you have a preference? Do you prefer being a robot or just floating around — your brain floating around in some fashion?

Do you know what I’d like? If it was really all possible, there were no limits or boundaries, I would like to do both. I would like to be able to enter a physical self sometimes.

A human body. Like a human body, not a robot.

Yeah, but not necessarily a biological body.

Oh, all right. So, what?

It doesn’t have to be a biological body. It’s like Iron Man, so we’ll have a stronger arm, we can run faster. So those are possibilities to extend what we are, so it might be.

You know, if I’m trapped in your computer, which is a bit of a genie-in-the-bottle story, and you’re really not letting me out, but eventually you say, O.K., Jeanette, you can come out, have a body, what will I choose? I don’t know.

But I like the idea that my consciousness could continue. But then of course I do, because I was brought up in a strict religious household. So deep inside me is a comfort with the idea that, no, this is not the end.

You do sound like a lot of venture capitalists I hang out with in San Francisco in many ways — or different — or Elon Musk, or someone like that. So that’s — I’m going to get back to that in a minute. But let me read to you from yourself.

“It’s all a fiction until it’s a fact, the dream of flying, the dream of space travel, the dream of speaking to someone instantly across time and space, the dream of not dying or of returning, the dream of life forms not human but alongside the human.” Is this your conception of innovation, I guess? Innovation of humanity itself?

I’d like to think that this is not the last word. I hope that we are evolving. You know, we’ve started to understand that process, once you get away from the idea of a god-given, fully complete, flat-back human that just appears.

If we are evolving, then we should be able to move beyond this point, I think. And blending with our technology seems like a good idea. Look, we know that Elon Musk, with his Neuralink company, is already developing implants to go in the brain, whereby paraplegic or paralyzed persons can communicate directly with their device.

But we know it’s not going to end there. The idea is that you, me, and everybody we know will be able to connect directly with the internet, the internet of things. We’ll be able to ask a question in our head. We won’t have to Google it, look it up on the phone. The answer will come back. Larry Page at Google has talked about that. And of course, this revolving door will mean there is no privacy, because if all your thoughts can be overheard, then what’s left for autonomy or privacy in the sense that we have always known it?

But young people I talk to say, are you crazy? They know everything about you anyway. You just imagine that you’re private now. You’re not. That may be true.

Yes, although I do think that many people still shudder at the thought of artificial general intelligence, which you were talking about, which is the next superintelligence, essentially. You know, and all these movies are dystopian when you’re looking at these things. Do you have a shudder in there?

Because you are enthusiastic. I mean, I have a future that is a little less pretty, and we can talk about the present and what has happened now. But where comes your sunny toward this?

Look, I’m an optimist by temperament. If we continually focused on a kind of Armageddon, doom-laden, dystopian future — as now, with climate breakdown — that’s where we’re going. We’ve got to be realistic. But we also have to be optimistic and hope that we can use all our ingenuity, plus the ingenuity of the tools we’re creating, to get us into a better place than we are now.

That’s what I would like to see, and there is no reason to remake A.I. in our image. It isn’t born with a gender or a biological sex because it isn’t a biological entity. No, it doesn’t have a faith. It isn’t going to start a religious war. It’s not got a skin color.

All of the things that we’ve fought about over the whole course of humanity need not be present in the technology we are creating. The future is not a force-like gravity. It’s propositional. We make it up as we go along.

Society is propositional. Nothing is fixed. We can change it, unless — and this is the big one thing. If we tip the planet over, then we’re not going to be able to change anything. There’s going to be no artificial —

Right, environmentally

Yeah — general intelligence. It’s going to be nothing except fighting for a few scarce resources and trying to stay above the water level and not scorch ourselves to death. There’s no future if that happens. So I am completely realistic about that.

Well, if we don’t have bodies, there could be, you know.

We will get there, though. Because time is short, you know. We’re a little bit further away from that moment where we could just zoom off. You know, I think this is why the big guys are developing their space rockets, isn’t it?

Yes, they are they’re trying to get the hell out of here. Yes.

They’re trying to get the hell out of here, yeah. Like that movie. What’s it called? “Elysium” —

Yes, “Elysium,” yes.

— where they’re all living up there, yeah. So we don’t want to do that.

Right. Let me just say, you pin a lot of hope on A.I. and a better future. I am of a belief that A.I. is us. Crap in, crap out. You’re more — crap in, better world out. So let’s debate that. Because one of the things you wrote — “connectivity is what computing revolution has offered us.” Absolutely true. “And if we could get it right, we end the delusion of separate silos of value and existence, we might end our anxiety about intelligence.” Here we have the Facebook Papers everywhere, and a lot of internal proof that there are some bumps along the road to perfection in technology.

I should say so, yeah. Look, I don’t have a Facebook account. I never have had. Because from the moment it came, I thought, this is like living in a Soviet tower block, where you’re encouraged to spy on your neighbor and hand over the dossier, and somebody’s quietly getting the data together. It’s just the capitalist version.

So that has never been for me, and I have very serious doubts about its utility in the world — certainly, its beneficial status in the world. Does it have one? I don’t know. But social media isn’t tech. It’s not just where we’re going. That’s not everything, and we shouldn’t just focus on that. And yeah, you’re right. Garbage in, garbage out. We know that all computers are trained on data sets. And if the data sets are flawed, which at present, they always are, then what we get is an amplification of bias or prejudice.

But in a strange way, it’s forced us to look at our own bias. Even people who thought, I’m not biased — we’re plugging those data sets into the machines and looking at what came out and thinking, I am biased. And that has really shown us something. It’s shown us that the most frightening ideologies are the hidden ideologies.

So not be scared of that— although sometimes I’d like to see some of it go away again and hide.

I’d like to see some of it go away.

Sort of like cicadas. Something like —

I know.

— 17 years it would be nice, if you’d all go away for a minute. I just interviewed Maria Ressa, who just won the Nobel Peace Prize. And one of the — she was quoting E.O. Wilson. “We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and god-like technology,” which she thought was a problem. How do you react to that concept of hers?

Of course. And it’s absolutely right. We have moved too fast for our emotional intelligence. And that’s partly why I wrote the book, because I knew that more people need to be involved in this conversation, that it shouldn’t just be left to the rich guys.

It’s not even government anymore, because this is not being run by any elected democratic institutions, is it? It’s being run by rich guys with a lot of power, and we can’t depend on their benevolence. I mean, most of the time, I don’t think they’re evil. I think they’re just overwhelmed with their own capacity, and they truly believe they have a vision of how the world should be.

I don’t think Facebook started out to be evil. I just think the whole thing could not work in the control of somebody like Zuckerberg, who’s got nothing in his history that suggests he can manage billions of people on the planet using his social media.

Right, absolutely. So in that vein, one of the things that was interesting — someone who does a lot of thinking of this is Elon Musk, obviously. Not just Neuralink, but all kinds of things, with space travel.

He’s the one who is particularly scared of A.I. He’s told me this. A.I. does not need to hate us to destroy us. And he compared A.I. and humanity to, we’re in an anthill, and they’re building highways.

And when we run over an anthill, we don’t think that we’re being evil, that we’d kill the entire ant colony when we’re building a highway. And that’s how I look at A.I. to humanity.

Yeah. I don’t think we should imagine that this thing, if it gains any self-reflection, any self-awareness, has to behave exactly like we do. Most of what humans do is run by emotions — usually, negative emotions, usually, fear of some kind — either fear of needing more money, needing more power, needing more land, needing more people.

A.I. is not going to be motivated in the same way. So I think the indifference question is more likely. What are these human creatures that are just causing so much trouble?

But as the scientific community is split. There are those who say, no, A.I. will stay as a tool, a powerful tool, but it will never develop what we would call intelligence, certainly not consciousness. And I think it’s pretty much split down the line of which way it’s going to go.

You keep talking about not needing the body. So what would that be?

It would be consciousness. You know what it’s like? Even now, because of the way technology is advanced, many people don’t use their bodies at all in the real world.

They use cars and planes to transport their brains around. They lie their bodies down and watch the TV. They sit in front of their laptop.

I mean, everybody — you know, when I’m sitting down, thinking or writing, my body is there, but I’m not conscious of it. I don’t think anyone is. You’re in your thoughts. You’re in your imagination.

Our bodies were designed to do stuff, and we don’t really do stuff with them anymore. So you have the ludicrousness of gyms —

Ludicrousness of gyms? [CHUCKLES]

Well, it is ludicrous, isn’t it? I mean, the bodies that were designed to work are now part of the work we have to do in order to stay fit and healthy. That would have seemed crazy to our grandparents, that this is how we have to stay fit. So what exactly is the use of being embodied, I wonder?

Right. So how will A.G.I. change our concept of the afterlife? You mentioned this a lot. Like, we’ve talked about Silicon Valley’s obsession with immortality.

Microsoft filed a patent to build chatbots of people, dead are alive, using their social media data. This was an episode of “Black Mirror,” by the way, which seems to anticipate everything. Do you think a chatbot could help with someone’s grief, for example?

Yes and no. It depends what you think grief is. And that in itself may change. I think, for the human condition, grief is something which must be felt. It takes time.

It always used to be two years. In the 19th century, people used to wear black for two years to say to people, I’m a little bit vulnerable, go easy with me. I think that was actually quite a good idea.

Now, you’re supposed to suddenly get over it in 12 weeks or you need to go to the doctor. That’s crazy. But is grief something that we should feel, mourn, understand, express, and then gradually move back into life without that person? I think it probably is.

In a way, if you think of consciousness as a pattern, at death, what happens is the pattern disappears. And on the other side of the pattern are the people that you made patterns with. And that’s why it’s so awkward for them, because their pattern-making is smashed up.

And you have to learn to make a new pattern, I think. And so it would be better to go through the grieving process and not use an app that replicates the dead person. It might help for a little while, you know, like sometimes.

But what if it was the dead person, not the app?

If it was the dead person, that would be different. Because if you mean, we’ve uploaded the consciousness of this person and they’re still around, that will be the beginning of some very different kinds of relationships between embodied and non-embodied entities.

Well, chasing immortality is about as close to playing god as it gets, right? And you wrote, quote, “What are we doing? In effect, we are creating a god figure, much smarter than we are, non-material, not subject to our frailties, who we hope will have answers.” But then, those answers are our own, correct?

Not necessarily. John McCarthy invented the term, artificial intelligence, back in 1956. I mean, I prefer to call it alternative intelligence, if we get there. I mean, I do want to be clear that at the moment, I know it’s a tool. It’s a brilliant tool, with Google’s DeepMind just solving the problem of protein folds last year.

So there are wonderful breakthroughs that are happening in the collaboration between humans and their smartest tool, which is A.I. But that’s all it is. But if it develops beyond being a tool, that’s the point where these questions become interesting.

And look, I’m not a computing scientist, I’m not a physicist, I’m not a mathematician. But I am sure the questions of how we develop the future should not just be left to people who are computing scientists, mathematicians, physicists, Silicon Valley guys, mostly because they are guys, and there’s a lot of white dudes in there. And we do need a more diverse base if we’re going to go forward. And that’s why I wanted to open the conversation a little bit.

Well, you actually opened it with Ada Lovelace, the English mathematician and writer, and Mary Shelley, the author of “Frankenstein.” And it’s notable these are two vanguard women in a field that today is largely dominated by men. It was interesting that you started with them.

And one of the lines I liked was, “poor Ada, told to study maths to avoid going poetically mad, then told she was at risk of going mathematically mad.” Can you talk about why you picked those two?

Those women were at the start of the future. You know, the Industrial Revolution, at the moment when repetitive work becomes mechanized, which was a great breakthrough, there’s Mary Shelley, writing about, in 200 years later, this idea of a far future that we couldn’t see at the time. And there’s Ada Lovelace, who was actually just born when Mary Shelley was writing “Frankenstein.”

Lord Byron was on that holiday on Lake Geneva in 1816. His estranged wife had just had a baby, called Ada. He would never see her. He didn’t want Ada to have anything to do with poetry.

It was a bit rich from Britain’s most famous poet, “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” So he gave instructions that Ada should be kept away from poetry, and her mother thought, what am I supposed to do? So she hired a maths tutor for her.

And from there, we know the story, that Ada, as she became Countess of Lovelace, got involved with Charles Babbage, the person who tried to design the world’s first mechanical computer, and she worked out that she could program it. She was highly sophisticated mathematically. And you read some of her things, and they are so far-sighted in terms of what she could imagine, just as what Mary Shelley could imagine.

And it was Alan Turing in 1950 who argued with Ada, Ada writing 100 years ago in 1950. Alan Turing writes a paper with a section in there called “Lady Lovelace’s Objection,” where he sits down and reads the dead Ada that nobody’s taking any notice of anymore because she’s a woman, and he says, was she right? And what he’s asking is, was she right about computing technology being able to originate anything, to be able, really, to think for itself?

Right. Just to be clear, Ada Lovelace thought computers and machines would not be able to originate intelligence.

Yeah, and that’s why he devised the Turing test, because he decided that Ada was not right. And as far as we know, nothing has passed it yet, the moment when we will simply not be able to distinguish between what is A.I. and what is human intelligence. But it fascinates me that Turing, a gay man, also an outsider —

Right, two women and a gay man were at the forefront of these thinking.

Yes. Yeah, because they were able to think outside.

Right.

And he was really the first person, for more than 100 years, to dust down Ada and have a look at what she actually said and realize how far-sighted she was. Because there’s a distorted history around computing technology, that women weren’t involved. Quite simply, it’s a lie. They were.

They were very early involved. So one of the things that it’s shifted to is why it then got taken over by men. And one of the things you write about a lot is sex, and you write a lot about health robots, which are robots that can help with a bunch of different tasks, versus A.I. sex dolls, which are, I guess, specialized. You paint sex dolls as an enemy of progress, and you like helper bots. So talk a little bit about this, because it’s a very man-like thing to create sex bots.

Yeah, it would appear so. I mean, in theory, there’s no difference, is there, with the platform between helper bots and sex bots. It’s just embodied technology that you can use around the house to help your kids with the schooling, help your grandma with dementia to get through the day. Because a bot doesn’t care if she says the same thing 500 times. You know, there’s something rather touching about that.

Bots will learn your memories and will respond. So I’m keen on it. And you know, anybody who’s ever had a relationship with their Teddy bear, which is all of us, will have a relationship with a little bot that comes and chats to you. How can we not? Humans form relationships. We can’t help it.

So I have no worries about that. Sex bots, I do have worries about, because it looks like a futuristic technology and a doll that talks to you and learns about your needs. But it’s bolted on to a very old-fashioned platform, and that is about gender, money, and power. It’s the usual stuff.

And it’s men who seem to want a kind of female act — I don’t really know how else to describe it — who will be a 1950s Stepford Wives style thing. She can’t go out of the home. She’s always pleased to see you. She never gets old. She never gets fat. She never has a period. She’s never going to eat the face off you when you’re late. She’s always ready for sex. She always comes when you do.

And we do wonder, if men have these dolls, how would they then manage in the real world with relationships with women who might be their boss, who might be their co-worker, who might be their client? What does it mean if you’re always coming home to this ever-ready female act that you have chosen over a human relationship? So I find that as a concept much more problematic than, say, a little iPal or a helper who’s about the house, doing things for you.

We’ll be back in a minute.

If you like this interview and want to hear others, follow us on your favorite podcast app. You’ll be able to catch up on “Sway” episodes you may have missed, like my conversation with Dave Eggers, and you’ll get new ones delivered directly to you. More with Jeanette Winterson after the break.

So one of the things — you talk about this idea of moving beyond the body, which you’ve talked about a lot again in “Frankissstein” and elsewhere, which is tech-optimistic, I would call it. Did the pandemic influence that optimism at all? Like, everyone obviously relied on it. It didn’t break, it worked, we needed it, et cetera. Because the pandemic obviously impacts the body, very clearly.

It does impact the body. I mean, I live in the countryside, and I’m a writer, so I’m used to isolation. So I didn’t miss any of the things that cities are good at that they became absolutely bad at when the pandemic happened. So I think I was better placed to manage it.

What I didn’t like, and I soon stopped, were the Zoom interactions with people I knew and loved. I found those dispiriting and disorienting. And you know, in China, there’s a group of people who call themselves two-dimensional, because they say that their significant life at work and at leisure is on the screen, and that their body, in fact, doesn’t matter at all and they’re not interested in it.

And many of them do have avatar personalities as well, because they think it’s the multiplicity of the mind, which is where the interest is. I can’t do that, even though I’m an enthusiast for moving beyond the body. As long as I’ve got what I’ve got, I’m living in it, and I’m looking after it. But I am prepared for and interested in a time when that might not be the case.

What about cryogenics? Aren’t you considering that idea?

No, I’m not considering that. I’m really not interested. If my time is up on planet Earth, if there isn’t a bridge to a bridge, if I don’t get there, then I’m fine to be out of here.

No, I’m not scared of dying. I’m not worried if there is anything beyond this, even though I was brought up religiously. I truly don’t care about that. When I’m gone, I’m gone.

But if there is a chance to do something else, then I’ll do it. But I do not want to have my head frozen in alcohol with the hope that I can be brought back and have a body replaced later. No, I’ll accept my fate, and I’ll go.

You know, I’m also interested in those Silicon Valley startups that say we will find a way of uploading your consciousness, but we know we’re a long, long way off that. On the other hand, 70 years ago, we couldn’t transplant a heart, and now we do many every day. We’ve moved so fast, we really have, from what was possible.

Well, you know, I always think everything we’ve imagined in movies is actually going to happen, if you look back. You know, Jules Verne, et cetera — it’s all —

I think you’re right. I think you’re right.

So one of the things that worries me, though, is the people monitoring this, the people who are responsible for this, I find less than stable, I would say. And it’s a nice way of saying I think they’re really screwed up quite a bit. So we’ve talked about big tech responsibility to our society.

I want your thoughts on the revelations of things — Facebook happens to be in the news. But it’s part of a lot more scrutiny over allegations, for example, that they knowingly put growth and profit over user safety when it came to the US presidential election, and across the globe, actually. Instagram’s effects on teens, these issues around India — it goes on. And obviously, right now, the whistleblower for Facebook who delivered a lot of these documents is speaking in Britain. Have you been paying attention to it?

I’m very much thinking about what’s happening here. You know, I think it goes back to something more fundamental than big tech. It’s about regulation. And that’s why I start, in “12 Bytes,” with the stories around the Industrial Revolution, which is where unbridled capitalism really kicks off.

And it’s also the moment in Manchester, my hometown, where you’ve got Karl Marx and Frederick Engels walking around. Why do they write the “Communist Manifesto?” Why does Marx do that then? Not because he’s a crazy commie, but because these are men who say, as Engels did, this is what happens when men are regarded only as useful objects.

And they looked at the misery, the squalor. Life expectancy was 30 years in the early Industrial Revolution. It was a living hell. History’s there so that we can look back and learn.

All this stuff now about, no, we shouldn’t have regulation, oh, we must have innovation, no, governments have no place in all this. Let everybody run ahead and do their own thing, and then we’ll work the problems out. They’ll move fast and break things.

What we should be looking at is saying, no, we do need regulation. We need to learn from the past. We cannot allow this to simply be directed by rich guys. This should not be in private hands.

So it does need very different solutions — and global solutions. You know, look, Ursula Von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, said earlier this year that we must urgently regulate big tech, stop it becoming this monopoly, and stop it having this malign effect.

Well —

Not intentionally malign, but malign.

Sometimes. I think sometimes it’s intentional.

I mean, I really don’t think anybody started out to do this in the way that it’s turned out. Maybe that’s optimistic.

I would agree with that. But I think with tons and tons of proof now, they continue down the same road.

They do. You’re absolutely right. And there’s no excuse for that. But that’s where we are now, you know. It’s got to stop, and it needs really strong government, but that needs to be backed by citizens like you, like me, just saying, we want this.

But what can regular non-tech people do? I just interviewed Dave Eggers, for example, and he talks about how convenience tends to win out. So does Margrethe Vestager — same thing — who is in the European Union.

That we all become complicit in it by ordering from Amazon. It’s easier, it’s better, it’s cheaper, et cetera. What do we have to do to hold ourselves responsible for the unintended consequences that these tech giants make?

There’s two things. One is we have to take responsibility to say, O.K., how does my behavior impact on the world? How can I be the change we want to see? We know how to do that. We can work it out. We can change our habits.

We can also learn from our kids, who are often holding their parents to account and telling us how to behave better, which I really appreciate. That’s important. But at the same time, we shouldn’t fall for the seductions of big oil.

When they invented carbon footprint, they were really saying, oh, it’s not our fault. We’re just giving you what you want. You change the way you live, and we don’t have to do anything.

That was just smoke and mirrors, and seductions of the worst kind. Yes, each of us is individually responsible and, I believe, can make significant changes. But we also have to be aware and not passive.

And we’ve gotten very passive. We think somebody else will sort this out, somebody else will solve it. That’s not going to happen. So it is about voting with your feet, saying no, I won’t support this company, I will support that company, but also trying to hold governments to account and say to them, you know what, we would like more legislation. We will pay more tax.

You know, we’ve got the rhetoric wrong. The story we’re telling now is not a story that’s going to help us to go forward.

So one of the things Facebook is trying to do is distract everyone with this metaverse push and possible name change. And I’m not sure if this is the company we want to build the metaverse. In fact, I’m certain it’s not.

I’m with you there.

But I’m curious what you think. What do you think about this idea of the metaverse where we live in this all the time?

I know. I think it is a distraction. I think what people could do with now is some really simple basic solutions to how we’re going to bring down the temperature and help with global warming. There’s stuff we need to do, which is not about fancy concepts.

It’s not even about really big solutions. It’s a matter of governments and big corporations to look at the facts, not the magical thinking, and say, we need to start making these changes. And I believe people would come on board. I think a lot of people in the world are very uneasy about this moment and would like to be part of the solution. They don’t want to be part of the problem.

Right, so it’s — some of them do.

Yeah, some of them do. But a lot of just your Ordinary Joes, your decent folks — I know they’re struggling to manage. But they would prefer — they have kids. They want to see a world for their kids. If they had a story that said, this is what we can do, all of us, and we’re all going to do it together, then that would start to change things.

So your book ends in an interesting place. You say humanity’s biggest problem is love. What do you mean by that?

I mean, I was trying to move past, I think, one of the disasters of the Enlightenment, which really is the René Descartes maxim that everybody knows — I think, therefore I am — that the definition of a human is the thinking, rational, logical capacity.

And that hasn’t been great, because you cannot split the mind and the body like that. You cannot split the head and the heart like that. It’s the worst possible binary. We know you can’t have a thought without a feeling.

And what we need now, I think, is to bring in a more compassionate response to the rest of the planet, to whoever else we share the planet with, and work out how we’re going to stay here and make it function. With or without A.I., this is our only home. We’re not going into space anytime soon. Not many of us, not in a viable way.

We did talk about space very briefly. If you had to go up into space with one of these guys, which one would you pick? Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, or Richard Branson? And you don’t get to come back. You have to live on Mars with them.

What, forever?

That’s your next novel, just so you know. But go ahead, yeah.

[WINTERSON CHUCKLES] Well, until your body breaks down and you need to be, you know, disembodied. But —

O.K. Well, I can’t go anywhere with Jeff Bezos.

Why? (LAUGHING) Why? You have to say why.

Oh. [LAUGHS] Because the Amazon model is just wrong. It’s wrong, and I don’t want to buy into that.

And also, his rocket’s shaped like a penis. But go ahead. Keep going.

Oh, I know, that’s just ludicrous. I don’t think he’s got any self-reflection. You couldn’t build a rocket like that, could you, if you had any self-reflection?

Yeah.

So he’d just talk about himself all the time, and that would be awful. Elon Musk is an interesting guy. I think he does have a utopian vision. There’s a lot about Tesla, which interests me. But would I want to spend time on Mars with him? No. I suppose I’d choose Richard Branson, because he would probably be able to do more than talk about himself.

All right, so the funny — the fun guy is who you’re going for?

I’d go for Branson. You know, he’s British, so maybe we’d get on a bit better.

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, sticking with the Brits.

If Branson doesn’t want to come with me, then O.K., I’ll go with Elon Musk.

All right, this has been great. Jeanette Winterson, thank you so much. It’s such a delight to talk to you.

Thank you. [MUSIC PLAYING]

“Sway” is a production of New York Times Opinion. It’s produced by Nayeema Raza, Blakeney Schick, Daphne Chen, and Caitlin O’Keefe; edited by Nayeema Raza, with original music by Isaac Jones, mixing by Sonia Herrero, and Carole Sabouraud, and fact-checking by Kate Sinclair. Special thanks to Shannon Busta, Kristin Lin, and Mahima Chablani.

If you’re in a podcast app already, you know how to get your podcasts, so follow this one. If you’re listening on The Times website and want to get each new episode of “Sway” delivered to you, along with a one-way ticket to Mars alongside the fun billionaire, Richard Branson, download any podcast app, then search for “Sway” and follow the show. We release every Monday and Thursday. Thanks for listening.

You can read the full article from the source HERE.

-

Sale!

Aurora: Tender Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,799.00.$2,599.00Current price is: $2,599.00. Buy Now -

Sale!

Dominique: Thick Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,499.00.$2,199.00Current price is: $2,199.00. Buy Now -

Sale!

Auburn: Red Head Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,199.00.$1,899.00Current price is: $1,899.00. Buy Now