Virtual reality could help treat sexual aversion and other sex-related disorders

A boom in new technologies is revolutionizing the field of mental health in terms of understanding and treating mental disorders like phobias, eating disorders or psychosis. Among these innovations, virtual reality (VR) is a powerful tool that provides individuals with new learning experiences, increasing their psychological well-being.

Immersive VR creates interactive computer-generated worlds that expose users to sensory perceptions that mimic those experienced in the “real” world.

People have found new ways to satisfy their sexual and emotional needs through technology; examples include virtual or augmented reality, teledildonics (sex toys that can be controlled through the internet) and dating apps. However, research on the use of VR in sex therapy is still in its infancy.

Read more:

Cybersex, erotic tech and virtual intimacy are on the rise during COVID-19

Sexual aversion is the experience of fear, disgust and avoidance when exposed to sexual cues and contexts. A Dutch study published in 2006 found that sexual aversion affects up to 30 per cent of individuals at some point in their lives. And a recent Québec-based survey of 1,933 people conducted by our laboratory revealed that at least six per cent of women and three per cent of men have experienced sexual aversion in the last six months.

These data suggest that sexual aversion is as common as depression and anxiety disorders.

Exposure and sexual aversion

Difficulties in experiencing sexuality with pleasure, whether solo or partnered, are at the heart of sexual aversion. Recovering from such difficulties involves changing one’s thoughts, reactions and behaviours in sexual and romantic situations by, for instance, gradually exposing oneself to apprehensive sexual contexts.

Recent findings suggest that VR could bring about such changes in real-life situations, particularly in individuals with poor sexual functioning or with a history of sexual trauma. Our own findings, not yet published, show that VR can help with intimacy-related fears and anxiety.

Immersive and realistic computer-generated worlds in VR could lead to positive sexual health outcomes such as increased pleasure and sexual well-being by alleviating psychological distress in sexual contexts.

(Shutterstock)

Treatment for sexual aversion involves controlled, progressive and repeated exposure to anxiety-provoking sexual contexts. These exposures aim to gradually reduce fear and sexual avoidance, two common reactions to sexual cues in sexually aversive individuals.

With this objective in mind, VR offers an ideal and ethical medium for intervention, as simulations can be tailored to different levels of sexual explicitness and be repeatedly experienced, even for sexual contexts that would be impossible or unsafe to recreate in real life or in therapy settings.

For instance, situations commonly feared by individuals with sexual aversion, such as sexual assault, failure or rejection, or feeling trapped in a sexual encounter, do not actually happen in VR. VR would not only allow them to overcome fears, but also to learn new sexual skills to use in real-world situations — skills that would otherwise be difficult, if not impossible, to develop. Individuals in treatment could then apply these learnings to real-world intimate situations.

Further, although people’s minds and bodies behave as though the virtual environment in which they are immersed is real, individuals are more willing to face difficult situations in VR than in the real world because they are aware that the former are fictional, and therefore safer.

Treating sexual aversion

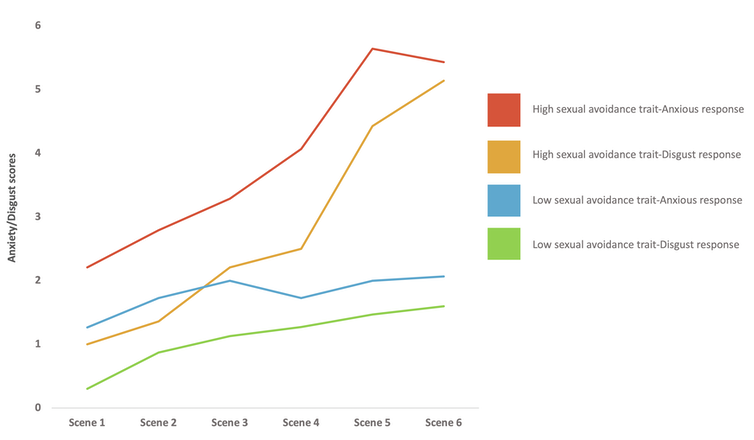

In December 2020, we collected data that allowed us to compare sexually aversive and non-aversive individuals. Participants were immersed in a virtual environment simulating a typical intimate interaction, which involved a fictional character engaging in sexual behaviours throughout six scenes. Throughout the scenes, participants were gradually exposed to the character’s flirting, nudity, masturbation and orgasm. Our findings suggest VR could represent a promising avenue for treating sexual aversion.

SOURCE, Author provided

Sexually aversive and avoidant individuals reported more disgust and anxiety than non-aversive participants in response to the simulation. And the more the scenes were sexually explicit, the higher the participants’ levels of disgust and anxiety. These results suggest that the virtual environment adequately replicated real-life contexts that would typically induce sexual aversion.

Future/futuristic treatments

Treatment options for people with sexual aversion could include exposure to tailored and diverse sexual contexts — for example, rejection, intercourse, sexual communication, attempted assault — through VR. This could help to alleviate distress and support positive and rewarding erotic encounters in real-life settings.

Applications of VR in sex therapy will be profoundly shaped by advancements in artificial intelligence. Hence, using erobots (artificial erotic agents) in virtual interactive environments to simulate realistic romantic and erotic encounters, which are often avoided by sexually aversive people. Virtual agents could also be used to develop sexual skills, explore sexual preferences and get reacquainted with one’s body and sexuality.

Read more:

Beyond sex robots: Erobotics explores erotic human-machine interactions

As VR can be used outside the therapist’s office, it could be included in self-treatment programs for sexual difficulties. With high-quality and affordable VR equipment entering the consumer market, future therapeutic VR protocols in sex therapy could be used in the comfort and privacy of one’s own home, promoting autonomy and improving access to treatment.

You can read the full article from The Conversation.

-

Sale!

Aurora: Tender Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,799.00.$2,599.00Current price is: $2,599.00. Buy Now -

Sale!

Dominique: Thick Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,499.00.$2,199.00Current price is: $2,199.00. Buy Now -

Sale!

Auburn: Red Head Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,199.00.$1,899.00Current price is: $1,899.00. Buy Now