Don’t worry about sex robots. They won’t ruin sex.

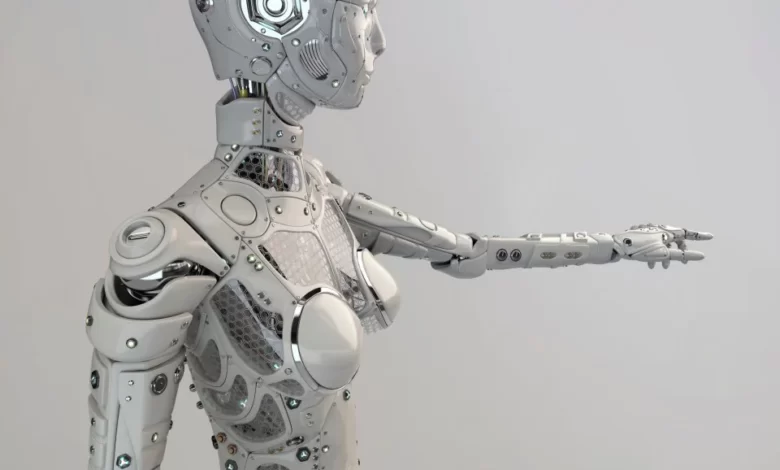

From Alicia Vikander’s pillow-lipped android Ava in “Ex Machina” to Scarlett Johansson’s sultry iOS assistant in “Her,” pop culture has long been fascinated by the idea of humans copulating with robots. While the sexbots in question are occasionally male (remember Jude Law’s dreamy gigolo in “A.I.”?), these fantasies are largely female-centric, depicting a future in which multi-orgasmic female robots will submit to men’s sexual whims at a push of the button.

While this brave new world of man-on-hardware action might sound exciting to some, many people are freaking the eff out over it. The dawn of the sexbots has been referred to as “the end of intimacy,” as well as “the impending demise of the human species.” Some of these arguments are based in feminism: Robotics lawyer Sinziana Gutiu, for instance, has argued that sexbots, because they are not capable of saying no, will inspire men to rape women by “promot[ing] users’ antisocial practices and impair[ing] the dignity of women.” Others seem to be opposed to sex robots on the grounds that they’ll simply be too good at sex. Robotics expert Joel Snell of Kirkwood College has warned that sex robots will become so “addictive” that humans will never want to boink other humans again.

Anti-sexbot sentiment is so intense that it has even prompted a feminist grass-roots collective, the Campaign Against Sex Robots. In its mission statement, the organization equates the relationship between a sex robot and its owner to that of a john and a non-consenting prostitute, breathlessly warning that sex robots will “reduce human empathy,” “reinforce power relations of inequality and violence” and “sexually [objectify] women and children.”

Yet despite this concern, there’s good reason why we shouldn’t fear the dawn of the sexbots. Our collective freakout over sex robots is yet another example of how our culture is terrified of technology — even though history has consistently proved that technology in the bedroom is rarely, if ever, something to be feared.

From cultural commentators writing alarmist think pieces about how Tinder is ruining our sex lives to men panicking about their girlfriends’ vibrators to parents wringing their hands over their kids watching online porn, there’s a precedent for our anxiety over sex and technology. (And let’s not even mention how John Legend and Chrissy Teigen are setting unrealistic romantic expectations for us on Instagram.)

Some of this concern is, to a degree, justifiable. It’s true that the widespread availability of online porn, for instance, has changed the game in terms of how we learn about sex. Many studies have concluded that sites such as Pornhub have essentially supplanted traditional sex education, resulting in young people having unrealistic expectations about sex.

Yet when you take a close look at many of the claims being made about sex and technology, it’s clear that much of the panic is baseless. Take, for instance, our obsession with how hookup apps are ruining our sex lives. While numerous media reports have claimed that Tinder and Grindr are causing rampant promiscuity, citing spikes in sexually transmitted diseases in various states, on the national scale, there’s zero evidence to suggest that Tinder and Grindr are directly responsible for the spread of STDs, nor is there any evidence to suggest that young people are having unprotected sex at such an alarming rate that STDs are on the rise.

On the contrary, the nation’s most common STD, chlamydia, is actually on the decline for the first time in three decades. Teen pregnancy and HIV rates are also falling, and where STDs are on the rise, a 2013 British study attributed it to an increase in people getting tested, not to an increase in people having unprotected sex.

Keeping our history of technophobia in mind, the sex-robot hysteria doesn’t make a whole lot of sense — especially when you consider that sexbots, in their ultra-sophisticated “Ex Machina” form, don’t actually exist yet. Despite pop culture’s sci-fi-infused visions of big-breasted, lingerie-clad fembots, most of our current options for sex robots aren’t actually that sexy to begin with. Most of them look less like Alicia Vikander and more like Rosie from “The Jetsons.”

Take, for instance, Roxxxy TrueCompanion, who has been marketed as “the world’s first sex robot”: While Roxxxy has a “heartbeat,” a “circulatory system” and a vaguely human-like personality, such as “S&M Susan” or “Wild Wendy,” the doll’s vacant gaze and waxy skin give it the appearance of a janky hair salon mannequin, not a human sex partner. (It’s worth noting that the doll is also prohibitively expensive, with a price tag of $9,995.)

Assuming, however, that the technology used to build sex robots will one day be advanced enough to make such products affordable, realistic-looking and readily available, there’s still the nagging question: Will they permanently alter the way we have sex? Maybe the better question, though, is would it be so bad if they did?

For those of us who don’t, for whatever reason, consistently have sex with human partners, sex robots might prove beneficial — not just as a masturbatory aid, but as a source of intimacy. “Sex robots will make possible ‘good sex’ or ‘plain sex’ for persons and populations otherwise separated from and/or unable to attract a romantic partner,” says Charles M. Ess, a professor of media studies at the University of Oslo.

To an extent, there’s existing technology that is already doing this, albeit in nonsexual forms: The robotic seal Paro (as seen on Netflix’s “Master of None”) is currently used to treat depression in the elderly. For people with conditions that make finding sexual partners difficult, it’s not unreasonable to presume that sex robots could one day play a similar role for them, providing both emotional support and a form of instant sexual relief.

It’s also possible to imagine a world in which sex robots could be used as an education tool, one that surpasses those now offered by hard-core pornography or our appallingly bad sex-education system. Imagine, for instance, a future in which sex robots can teach the value of foreplay by simulating clitoral orgasm, or if they could instruct people with Asperger’s on the value of nonsexual touch by snuggling with them in bed.

Of course, it’s important to note that sex robots won’t be able to provide one crucial thing that a human partner can: informed consent. To many feminists, having sex with a piece of hardware that is unable to provide consent encourages men to view sex as a commodity, while the “sellers of sex are not attributed subjectivity and reduced to a thing,” according to the Campaign Against Sex Robots. (The Campaign Against Sex Robots does not appear to acknowledge the possibility that sex robots might also exist to please women, even though companies such as RealDoll are already offering male versions for gay or female customers.)

Even though on-demand sex already exists in the form of online porn and escorting apps such as Ohlala, it’s admittedly unsettling to envision a future where men can purchase a big-breasted plastic woman online and use her to his own ends, even if that woman is incapable of thinking or feeling. That feeling of discomfort is magnified by reports of so-called child sex robots, which have been suggested as a possible therapeutic tool to help pedophiles divert their sexual attraction to children.

No one wants to live in a world where there is a demand for things like child sex robots, because no one wants to live in a world where men have the urge to rape and mistreat women and children. But we already live in such a world. Many clinical psychologists believe that pedophilia is a fixed sexual orientation, so their goal is not to eliminate pedophiles’ sexual attraction to children, but to teach them not to act on their urges. Whether we like it or not, child sex robots could potentially serve as such an outlet, thus preventing real children from being put in harm’s way.

It’s not clear at this point whether sex robots would be a successful therapeutic tool for pedophiles or if they would merely encourage such desires to blossom. (Past studies on increased statewide access to online porn has been correlated with a decrease in sexual assaults, although there’s little consensus in the scientific community to bolster the hypothesis that porn in general serves as an outlet for deviant sexual desires.) Yet to dismiss offhand the mere possibility that sex robots could serve a greater good not only does innovators in the field of artificial intelligence a disservice, but also society at large. If technology exists to serve society’s needs, then it’s worth identifying what those needs are and how sex robots can best serve them, regardless of how uncomfortable such a conversation makes us.

Visions of a “Westworld”-esque dystopia where the machines ultimately turn on us aside, the anxiety over the dawn of the sex robots is an all-too-familiar story: It’s a fear of technology, masquerading as genuine concern over preserving sexual mores.

“There is nothing more central to our sense of identity and our moral or ethical sensibilities than matters of gender and sexuality,” Ess said. “So the advent of sex robots immediately threatens to disrupt and alter our practices, norms, sense of identity, et cetera.”

Now let’s stop freaking out over sex robots and get back to rage-clicking through Chrissy Teigen and John Legend’s Instagram photos, because come on, there’s no way those two are nearly as happy as they appear to be.

You can read the full article from the source HERE.

-

Sale!

Aurora: Tender Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,799.00.$2,599.00Current price is: $2,599.00. Buy Now -

Sale!

Dominique: Thick Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,499.00.$2,199.00Current price is: $2,199.00. Buy Now -

Sale!

Auburn: Red Head Sex Doll

Original price was: $2,199.00.$1,899.00Current price is: $1,899.00. Buy Now